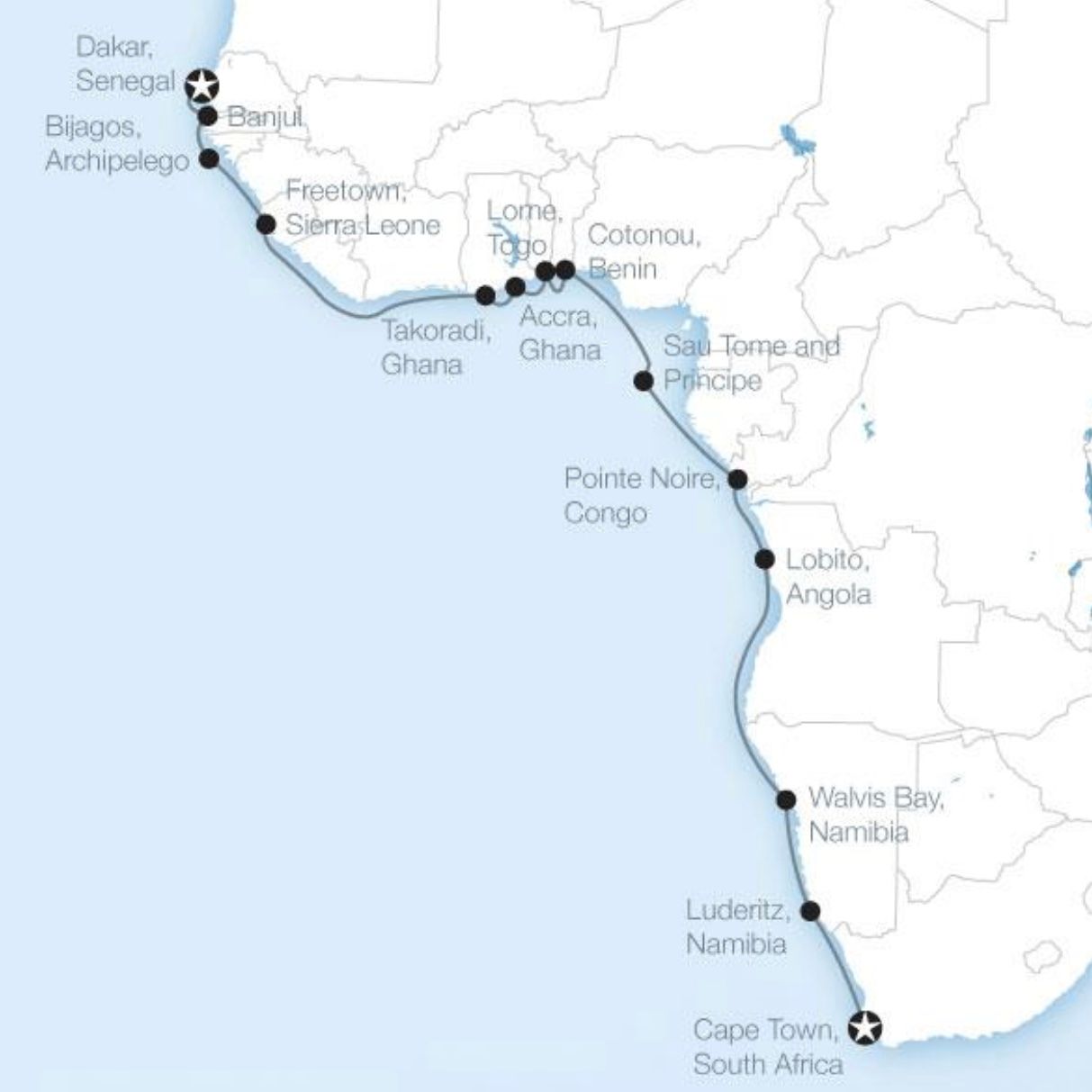

My journey to Guinea-Bissau really started way back in April 2013. I was travelling up the west African coast on an adventure cruise with GAdventures.

In the final week of the cruise we were due to visit the Bijagos Archipelago in Guinea-Bissau. However, the day before we were due to arrive it was announced that we would not be visiting. Our entry had been denied.

There was no official explanation, just a throwaway comment from a liaison about the number of Americans in our group.

I was aware of a news report stating that the Guinea-Bissau naval chief had been arrested in ‘international waters’ by the US and had been extradited back to New York. He was charged with drug trafficking. This was obviously not some random arrest but a very successful sting operation.

I pointed this out and mentioned the probable diplomatic fallout between the two countries. This theory quickly spread. However, the main response from the Americans on board was laughter and jokes (except for the ‘country counters’ who were very upset that they couldn’t ‘tick’ Guinea-Bissau off their travel lists) I shook my head and privately wondered at the naivete of Americans even the minority that do travel outside their own country.

So we sailed on by the Bijagos Archipelago and onto Banjul in The Gambia.

If you read my post on Cabo Verde you'll already know that the long and bloody fight for independence in Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau was waged in Guinea by the The African Party for the Independence of Guinea-Bissau & Cape Verde (PAIGC) led by a charismatic freedom fighter named Amilcar Cabral.

He was assassinated in Conakry in 1973 by two members of his own party, but by then victory was inevitable and Guinea-Bissau achieved independence in 1974 closely followed by Cape Verde in 1975.

Three of Cabral’s PAIGC comrades assumed strategic positions of power. Luis Almeida Cabral (Amilcar’s half-brother) who became the first President of Guinea-Bissau, Aristides Pereira who became the first President of Cape Verde, and Joao ‘Nino’ Vieria who became the commander in chief of the armed forces of Guinea-Bissau.

All was not well in Guinea-Bissau or in the PAIGC. In July 1980, Vieira led a military coup against Almeida Cabral, who was charged with abuse of power and sentenced to death. He was able to negotiate a deal where the charges were dropped in exchange for his departure from Guinea-Bissau. He left and went into exile.

The coup was resented in Cape Verde, which severed military and political links between the two countries. Amilcar Cabral’s dream of the ultimate unification of the two countries was shattered.

Vieira stayed in power until 1999, and then he too went into exile. Earlier, in 1998, he had dismissed the military chief of staff, Brigadier Mane, who promptly launched a revolt. The unrest spread, spiraling into a civil war. Troops from Guinea, Nigeria, Senegal and France intervened, and fresh elections were held. For the first time since independence a non-PAIGC Government was elected to office. However, in 2003, President Iala was removed in a ‘bloodless coup’.

By 2005, Vieira had returned from exile. He was returned to power the same year but little had changed. In 2008, he survived an attempted coup, but his luck ran out in March 2009 when he was assassinated by soldiers (who denied that they were seizing power).

Fresh elections were called, but the bloodshed continued. In June, the military assassinated a Presidential candidate, a former defense minister, a former Prime Minister (and others) claiming that these people were plotting to ‘overthrow the government’.

On the day that I arrived, the country had just held democratic elections. The news reports televised in Dakar Airport said that the mood was peaceful and calm. Even so, the Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS) had already pledged to place an army on standby in the country to ‘prevent a coup’.

It turns out that if no one wins more than 50 percent of the vote then a runoff ballot will be held later this year between the top two candidates.

Although not much has changed in the past ten years, there have been small gains, the incumbent President is the first in 25 years to finish his term and I read a report that there hasn’t been a coup since 2012.

Yesterday I saw a Government vehicle travelling under heavy military guard (eight scary, heavily armed tactical soldiers dressed in black) and then I saw an Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) parked near the Presidential Palace. If history here has shown anything, it’s that you can never be too safe.

In the years since independence the fate of the two countries (once destined to be united as one) have diverged. While Cape Verde is one of only five countries to have ever graduated from the UN’s least developed countries (LDC) list Guinea-Bissau has remained at the bottom of the UN’s human development index (HDI). The HDI is an average measure of human development achievements (including life expectancy, education and standards of living).

Guinea-Bissau ranks 177 out of 189 countries. To give you some idea of what this means, a male child born in this country will have a life expectancy of 52 years, that’s if he makes it past infancy (as infant mortality rates are high)

And if all that’s not bad enough throw some drugs into the mix. Well, actually throw in a lot of drugs.

Let’s go back to 2013 and the arrest of the Naval chief by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), which was closely followed by the indictment of Guinea-Bissau’s head of the army.

Guinea-Bissau had been identified as the West African transit point in the cocaine trade and its highest government officials were implicated. The Americans labeled both of these men 'drug kingpins’.

Poverty and corruption have proven fertile ground when it came to establishing a West Africa transit point for drugs, but add to that the porous border, 88 islands (many uninhabited) and a powerful military and you can see why The Economist magazine calls Guinea-Bissau ‘Africa’s most famous narco-state’!

As a postscript to the original story, the Navy Chief served out his four year sentence in the US and returned to Guinea-Bissau in 2016. He formally approached the Government and asked if he could resume his military career, explaining that ‘I am a veteran of this country’s war of independence, I gave everything for this country’.

My late arrival into Bissau is met with darkness. The poorly maintained roads are illuminated by the headlights of vehicles, and only small sections of road have street lights. This doesn’t deter the people. There are many out walking, buying, selling. They flash briefly into view before disappearing back into the darkness like ghosts.

It is only later, when I am returning to the Airport, that I realise that on this night we have taken a back road into the City. The main road is sealed, well maintained and lit, with many new buildings lining that route.

My hotel is situated in the Bissau Velho, the Old Town area. The colonial buildings date back to the Portuguese occupation and have a faded charm, but the infrastructure in the centre is aging and poorly maintained.

The Coimbra Hotel is a charming old colonial building. It is bursting with books and art. The reception area, the dining room and the narrow hallways outside my room have bookshelves crammed with books. The walls are covered with framed artwork. There’s a restaurant downstairs and a shaded courtyard area. Later, I find a bookstore downstairs at street level.

The traffic here isn’t bad. There are many blue and white taxis on the street to compensate and they all beep their horns and slow down in anticipation of a fare. The main arterial roads are sealed but there are many potholes. Same deal with the side streets only some aren’t sealed. There are concrete and paved footpaths so the area is somewhat pedestrian friendly.

I arrived on a mission. I spent my first morning walking around looking for Embassies. It’s quite a challenge as there are no street signs as I know it, but if you’re lucky (and observant) the name of the street may be printed on a brick wall or fence or on a business sign. I walked straight past the Guinea Embassy but doubled back when I looked up and recognized their flag flying over the fence!

There are large, well established trees planted along the streets and they provide a welcome reprieve from the midday heat. During the day people are milling about everywhere. Some are outside sweeping the paths clear of debris. Many park themselves on the footpath with goods to sell; fresh fruit is popular and I also saw traders walking around with food, drinks, watches, clothing, even live chickens. The ladies carry heavy wares in baskets African-style, balanced on their heads.

The area looks worse than it is. I mean to say it looks unsafe but it actually isn’t. That’s the common stereotype of poor places, I guess. I can’t say whether it’s usually like this or whether it’s due to the elections and the increased police and military presence. I haven’t seen another tourist yet but maybe they’ve decided to bypass Bissau and head straight to the islands.

It’s a shame that on this trip I won't have the time to explore the islands, which are a real tourist draw card; one is famous for its ocean dwelling hippos!

By late afternoon, the Old Town empties of cars and people and the old buildings glow in the dying rays of the sun. It is then that you catch glimpses of the beautiful city that it once was, that it still could be.

Even so, the Old Town, and the country, is in a sad state. Poor Amilcar Cabral, whose mausoleum sits in the nearby Fortaleza d’Amura, maybe it’s for the best that he never lived to see this: his people freed from the tyranny of colonialism only to endure the greed and ambition of the men who once fought beside him.

Where on earth....